What does the Nanjing Yangtze Bridge and Mt. Fuji have in common? There are several differences. Their countries, China and Japan respectively, have been at cultural and political odds for decades, and both are notoriously wary of being compared to the other. With one landmark being a forty-eight year old bridge, and the other central to it’s nation’s culture, there is very little to compare.

Only one thing binds these two disparate locales — Suicide. In its entire history, the Nanjing bridge has documented over two thousand suicides. This number became the world record-holder in 2006, taking over for San Francisco’s Golden Gate Bridge. At the time, the bay area’s iconic landmark had documented approximately 1,500 cases.

Now how does Mount Fuji fit into this issue? In 864 CE, the volcano erupted on its northeast side. Producing a large amount of lava, the expelled elements pooled into a nearby lake, known as the Semouni (せの海). As the lava cooled, the lake was gone, replaced with a plain of dried rock. 1,152 years later, that rock plain has grown to become a thickly grown forest of ill-repute.

Known as Aokigahara Jukai (青木ヶ原 樹海), the forest has unfortunately become a frequent site for suicide. Colloquially, the forest has also been dubbed the grimly titled, Suicide Forest. Although there hasn’t been an aggregate accounting of the statistics, similar to other common sites, it is estimated that there has been at least 30 completed acts annually since 1988. So far, the annual record belongs to 2003, where 105 bodies required cutting down.

It was not a matter of convenience that led Aokigahara to acquire such notoriety, but rather superstition and subsequent reputation. Having grown on lava rock, the forest is both immensely fertile and dangerously unbalanced. As such, the trees are multitudinous and dense, while there is no trail to particularly speak of. The ground can change gradient at the drop of a step, and potholes abound with uncomfortable frequency.

The result of such geologic madness? A true nightmare-scape. There is clearly a reason why films such as Keanu Reeves’ 47 Ronin, Gus Van Sant’s The Sea of Trees and Natalie Dormer’s The Forest, opted to use Aokigahara’s unique setting to tell their stories. The trees are grown so thick that very little light shines through. The challenging nature of the terrain creates a sense of disillusion, as though you will never make it out again, and will be lost in the mire for the rest of time. All together, there are few other places on the planet capable of eliciting such a sense of foreboding. The darkness, the unpredictability of the terrain, the reputation of the locale, it is no wonder that people of all walks opt to end their lives in such a place.

In Japanese culture, there was been a common method to explain away this feeling — angry spirits. As with everything affiliated with the forest, however, it is not that simple. Commonly cited in folklore, Aokigahara was reputedly the site for a feudal practice known as Ubasute (姥捨て). The Japanese equivalent to senicide, this act involved the abandonment of the elderly, especially in times of hardship, in the wilderness, as a variant of euthanasia. If familial resources were limited, the eldest members of the family would volunteer their lives in order to lessen the collective burden. Despite forming the basis for many cultural works, there is no concrete evidence to suggest that Ubasute was even a remotely common custom.

Facts, however, do not generally get in the way of a good legend. As those abandoned inevitably lost their lives, their spirits remained. Trapped in forest where they were left, they soon grew angry, becoming Yūrei (幽霊). Similar to western ghosts, these spirits are not able to move on, and thus seek vengeance. According to Japanese folklore, these angry spirits are what’s to blame for Aokigahara’s dark association with death and dying.

In June 2016, I took the time to visit the Suicide Forest myself. Taking the 1123FJ bus from Shinjuku to Kawaguchiko, I was immediately transported from Tokyo’s hyper-modern metropolis to a rural setting at the base of mount fuji. Otherwise known as the ‘Fuji Five Lakes’ region, this area is popular with tourists and Japanese locals looking for a weekend getaway. Comprised, obviously, of five bodies of water, the titular lakes are Kawaguchiko, Yamanakako, Shojiko, Motosuko and Saiko. The region’s high misty peaks, picturesque lakesides and rural aesthetics are reminiscent of the fjord regions along Norway’s coastline.

To reach the suicide forest with greatest ease, I caught a local bus to Lake Saiko. There is a stigma against visiting the site, unsurprisingly, so there wasn’t precisely an abundance of signs pointing me in the right direction. As I walked around near Lake Saiko’s shorefront, I got to speaking to an old gentleman selling a variety of dried fish snacks. After assuring him that my goal was not to end my life, he pointed to a nearby dirt path, saying that it would lead straight into the forest if I followed it for roughly 20 minutes.

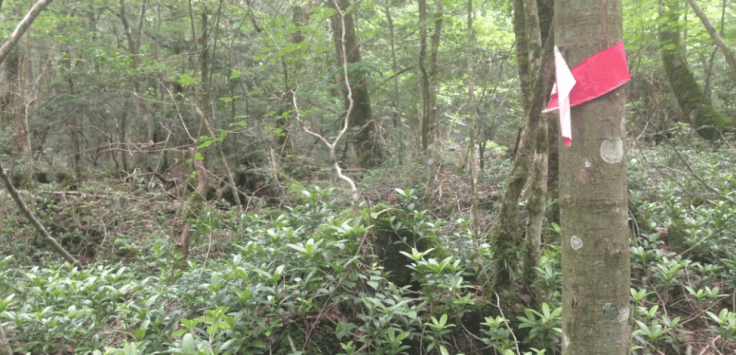

It was a reasonably bright day when I had arrived at the lake; a bit cloudy, but otherwise alright. As I walked along the path into Aokigahara, the trees grew denser, the path became overgrown and the environs became darker and stiller with every step. forty-five minutes of walking later, a sense a foreboding was unmissable. Granted, I was well aware of the history of the forest, but the lighting, sense of disorientation and complete silence lent itself to such a feeling.

What little amount of trail there was upon entering was gone by the time I reached the center of the forest. About 100 meters to the east of where I was standing, I could just barely make out what looked like a clearing. Even in the most ordinary of circumstances, I’m not the most graceful of people. At that moment, stumbling over uneven and unstable ground in a dark and dense forest, it was pretty embarrassing. Eventually though, I made it to my destination.

The tree trunk was mostly bare, exposing raw yellow bark. At its base, a ring of rotted black garbage bag. Looking up, the lowest branches were all snapped. The story told itself. A man likely hung himself from the tree after camping around the base. The garbage bag probably contained his necessary possessions, in case he chose to turn back. When his body was inevitably found and removed, the branches would need to be snapped in lieu of untying the noose. A dour and all-too-real account, to be sure, but one that illustrates that Aokigahara is more than a series of statistics and cultural folklore.

I had originally planned to camp in Aokigahara, spending two days really getting a feel for the place. After what I had seen in the clearing, however, I was ready to head back to civilization. I blundered about through the forest, looking for the exit. At that moment, the lack of a trail was a hinderance. Occasionally, there was a sign in Japanese, but that was no help. Ultimately, I just picked a direction and stuck with it. About an hour or so later, I was spit out at the side of a lonely mountain road, and walked until I found the official entrance. I had entered through the back, so there was only one way to head.

Eventually, I did indeed find what I was looking for. There were cars near the entrance, their windshield wipers filled with debris; The only indication to be had was that their owners hadn’t been back around in quite some time. A little ways down the path, signs abounded with warnings (in Kanji) against suicide — to think of one’s family, friends and ancestors.

Having spent four hours in Aokigahara Jukai’s grim surroundings, I was ready to return to Kawaguchiko’s pastorally quaint locale. Thankfully, and obviously, I did not contribute to the suicide forest’s fatal reputation. Having lived to tell the tale, I came away with nothing but an increased appreciation for the brighter things, as well as a sample of the lava rock forming the base of the Sea of Trees.

I really enjoyed this post jordan. What an interesting experience. U r way braver than i would have been – to venture in. I wonder if the forest has been included in the art of all the views of mt fuji….

So well written too !! Keep traveling!!

LikeLike