What does “going off the beaten path” mean? To the uninitiated, this could mean taking a different route home on the way from work, or going to the Ozarks, instead of the Grand Canyon, for a family trip. In any case, the essence is that adventurous steps have been taken into the unknown. In the context of a world traveler, who has already explored Bangladesh and Myanmar, the concept of going off the beaten path leads to Haiti.

Haiti has suffered an unfortunate image problem in recent decades. While tourism flourished in the 1970s and 1980s, it has been reduced to a mere fraction in the wake of several coups and the infamous 2010 earthquake. In the case of the latter, foreign visitation further decreased when a Cholera outbreak began in UN camps months later.

The media hasn’t helped either. With headlines predominantly featuring death tolls, chaos, and Christian charity, it’s almost understandable that people would be less than inclined to visit. Of course, Haiti is not for everyone, and I’m not suggesting that the families of the world converge on the island nation for their next summer getaway. What is important, however, is perspective.

Within the breadth of my travel experience, Haiti’s level of development, as well as its history of stability — or lack thereof — is not unique. There was nothing — and I mean nothing — in Haiti that I had not seen before in India, Laos, or Cambodia. Open air sewers, corrugated metal structures, overcrowded and hectic public transportation systems, and so on.

While there is an overabundance of memes and Game of Thrones theories on the internet, there is precious little about the specifics of traveling to Haiti as a backpacker. It is my aim to shed light on an under-appreciated country that could do with a bit of intrepid attention.

Port-au-Prince

It does not help matters that foreign governments advise against visiting Haiti. Complete with advisories against armed assault, kidnapping, protests, and public transportation, specifically in regards to the Port-au-Prince and southern regions, they make it sound as though Haiti is a life-ending tragedy waiting to happen. Full stop, I never felt unsafe in the capital, nor anywhere else in the country.

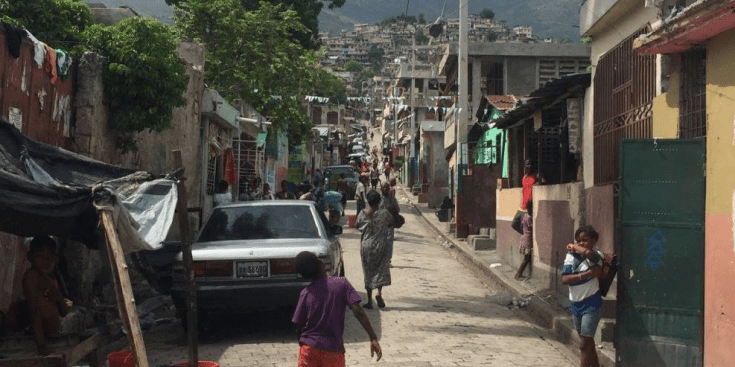

Port-au-Prince is a product of its circumstances. With much of its redevelopment funds squandered by the Red Cross, the effects of the earthquake are still evident, with nary a second story building in sight. Memorial park and its surrounding area, which once lay in front of the national palace, is now a loitering spot for the masses that are out of work while the national palace is a fenced-in pile of rubble.

Like similar locales in the Caribbean, such as Puerto Rico, the hotels act as barriers between visitors and the world beyond. With armed guards, thick walls, and strict curfews, one would think there was an imminent threat of siege. I stayed at the Park Hotel, in the memorial park area, which was more than able to cater to my backpacker sensibilities. The manager, Philip, not only arranged an affordable and efficient pickup from the airport, but was also able to put me in touch with a local guide.

Normally, I avoid using guides, as I prefer to take things in at my own measure and speed. In this case, where no English, Spanish, or Chinese was spoken, and Haitian Creole dominant, I would’ve had a pointlessly tough time going solo. Philip’s contact, George, was extremely cognizant of what I wanted out of Port-au-Prince. As a local expert on Voodoo practices, his tour was a mix of the mundane and the arcane to provide a picture of what Port-au-Prince looks like on a daily basis, at the local level.

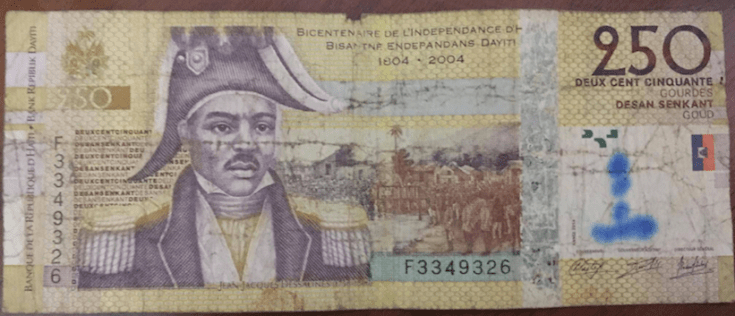

After he helped with the basics of exchanging dollars for Haitian Gourdes and securing appropriate SIM cards, George introduced me to a local voodoo priest by the name of ‘Emperor Nelson’. Mr. Nelson took me through an alley of an alley, before reaching his shrine. A small room filled with human skulls, bottles of whiskey, and ceremonial instruments, it was a clearly a place of spiritual significance for believers.

After preparing a ceremony, the Emperor lit a candle atop of one of the skulls. This was intended not only to summon dead spirits, but also to focus their external energies. After a number of chants, Nelson began talking in tongues, apparently possessed by one of the surrounding spirits. This is a major crux of voodoo religion, as opposed to the stereotypical stabbing of dolls in popular culture. This man before me, who was no longer Emperor Nelson, now went by the name of Amadie.

The first thing Amadie demanded was his whiskey. George took that moment to me that each whiskey bottle was tied to a specific spirit. Amadie liked Five Star Barbancourt with a small spritzing of baby powder. After telling me that I was a direct reincarnate of Saint John the warrior and that I wouldn’t die in the near future, he asked for a donation of 1500 Gourdes ($25 USD).

After leaving Amadie Nelson to check out the Iron Market, and taking a small break for Prestige Beer, we took a taptap up to Petionville. In an odd contrast, Petionville is Port-au-Prince’s upscale neighborhood. With Puma stores, modern shopping areas, global hotel chains, and foreign embassies — including Brazil, Switzerland, and Syria — it’s no wonder that this is that area that the United States embassy keeps the closest watch on. A large majority of it’s reported crime comes from this neighborhood, largely due to the money at stake.

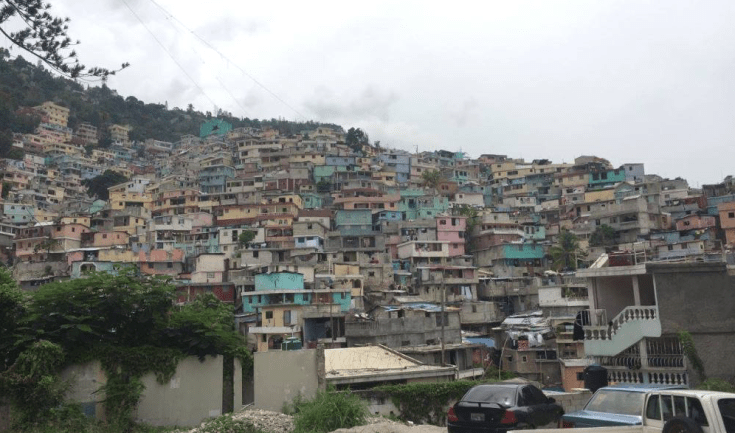

For evidence of the influence the money wields, without naming names, the patrons of a certain name brand hotel chain complained about their rooms having to look out on a nearby slum. Shortly thereafter, money was allocated to paint the front of every building in the neighborhood. Not the back, not the side, but the fronts that the wealthy visitors could see. It may be a facade, a shadow on the wall, but if one were to google image Port-au-Prince, the Jalousie neighborhood’s rainbow appearance will be one of the first results.

To wrap up the tour, George brought me to Hotel Oloffson. Constructed in the late 19th century, this establishment is truly of another era. With a veranda overlooking the city, expansive jungle-esque grounds, and a litany of high profile guests including Barry Goldwater, Truman Capote, Robert Kennedy, and Mick Jagger, the hotel more than lives up to its pedigree.

After a rum sour or two, it was time to wrap up the day. George did an incredible job taking us around the city. For a relatively inexpensive $60 for the day, his services were a steal. Should anyone wish to get in touch with him, Philip at the Park Hotel can be of assistance. In fact, George did such a good job that I decided to cut short my time in Port-au-Prince, as I had accomplished everything I’d set out to do. With that and another bit of Prestige, I headed north to Cap-Haïtien.

Cap–Haïtien

About ten years ago, it was hip to say that Haiti was 98% deforested. Such bold claims are easily refuted when looking out the window, along the road from Port-au-Prince to Cap-Haïtien. While not necessarily thick with jungle, the countryside provided a certain verdant splendor to the approximately seven-hour drive.

My first impression of Cap-Haïtien was that of stepping in a time warp. Gone was the urban decay that was Port-au-Prince. In its stead was a French colonial city along the lines of what New Orleans must have looked like two centuries ago, complete with broad avenues, a balcony or two within constant view, and tight streets packed with merchants.

Otherwise known as Au Cap, this city previously functioned as not only the capital of the Northern Haitian Kingdom from 1811 to 1820, but also for the whole of Saint-Domingue — Colonial Haiti — for a majority of the French occupation. That said, the city was originally settled by French pirates in the early 17th century. With those dates in mind, my first impression was off by a couple centuries, thus making the city all the more impressive.

Once I arrived in the city, I was met by the taxi driver employed by the hilltop hotel I was due to stay at, Habitation Des Lauriers. From the moment of my arrival, the view alone made everything worth it. When having breakfast in the morning, or a rum sour in the afternoon, the hotel’s many viewpoints gave those staying there an immaculate view of the city below.

Citadelle Laferrière and Palais Sans Souci – Background

If one has found his or herself in Haiti, especially in Cap-Haïtien, it would be a mistake to not see the country’s top historical locales — Citadelle Laferrière and Palais Sans Souci. For much of their existence, the situation in Haiti has been too volatile to encourage much tourism. However, the Citadelle holds the distinction of being largest fortification in the Western Hemisphere, and thus cannot be missed.

To understand the reason for their being, some history is required, especially as it concerns four notable men. Following the revolution to overthrow the French, the movement’s hero, Toussaint Louverture (one), named himself ‘Governor-General for Life’. ‘For Life’ ended up being only a year, however, when he made a deal with Napoleon Bonaparte’s returning forces to resign and be deported.

Following Toussaint Louverture’s departure, the mantle of revolutionary leader was up for grabs. Obviously, Toussaint’s top lieutenant, Jean-Jacques Dessalines (two), who purportedly orchestrated his downfall, was more than happy to take up the responsibility. In this newly acquired role, Dessalines declared Haitian independence on January 1, 1804.

It took only nine months of leadership for Dessalines to not only declare himself Governor-General for Life, but also Emperor of the first Haitian Empire. Again, however, ‘for life’ didn’t take too long, with the occasion of Dessalines’ assassination arriving a scant two years later.

With leadership in the nascent country again vacant, the masterminds behind the emperor’s demise took advantage of the chaos. As they could not satisfactorily agree on who should take complete power, these two men, Alexandre Pétion (three) and Henri Christophe (four), opted to split the country in half.

Pétion took the south, and named himself President of the first Haitian Republic, the capital of which was designated to be Port-au-Prince. Conversely, Henri Christophe took the north, with Cap-Haïtien as his capital. Initially establishing the State of Haiti, Christophe acted as president for the first five years of his reign.

As an officer of the initial revolution and general of forces upon the return of French forces in 1802 and 1805, Henri was understandably wary of the colonial power making another grab to reclaim the land they saw as their own.

He was never going to allow them to win and, thusly, his newly founded state needed to be prepared. As such, as one of his first acts, Henri commissioned the construction of a massive fortress, the likes of which the new world had not yet seen – The Citadelle Laferrière.

This wasn’t the only structure Henri had built. Amongst the nine palaces, fifteen châteaux, numerous forts and summer homes, he began to believe that he, as the leader, deserved a proper palace fit for a European monarch. Shortly after commissioning the palace, now known as Palais Sans Souci, President Henri unsurprisingly decided to rechristen himself Henri I of the Kingdom of Haiti.

Although he led as king for nine years, Henri I never got the opportunity to fully enjoy the completion of his greatest legacy. Around the time that Citadelle Laferrière was completed, in 1820, Henri suffered a major stroke and committed suicide shortly thereafter.

Citadelle Laferrière and Palais Sans Souci – Visiting

Back in present, there was no chance that I would miss an opportunity to witness these marvels of 19th-century engineering. In my case, from Cap-Haïtien, there were two ways visit the sites – taking public transportation or accepting a ride and tour from the son of Habitation Des Laurier’s owner.

Nine times out ten, when traveling, I opt in favor of public and local transport. In this case, however, the numerous connections, wait times, and transfers were too numerous to properly ensure ample time at the Citadelle and Palais.

It was wise that I opted to go with the tour, as the attractions are located just outside of a small town called Milot, which lies 20 kilometers south of Cap-Haïtien. The ride itself took roughly an hour, and I was grateful for the smooth process.

The process to get up to the Citadelle, even after arrival, is multi-fold. The Citadelle is located at the top of the mountain, and before the 40 climb, the purchase of a ticket is required. As I hiked up with my guide, the path we followed varied intermittently between rural solitude and roadside sellers.

As time passed, Citadelle Laferrière began to come into view, the true magnitude of its size quickly became apparent. With hundreds of cannons, a field comprised of piles of cannon balls, viewpoints that stretch from Cuba to the Dominican Republic, and a complete plumbing network, this fortress was clearly ready to fight the French army tooth and nail. In short, Citadelle Laferrière was only a dragon or two short of being suitable for Daenerys Targaryen.

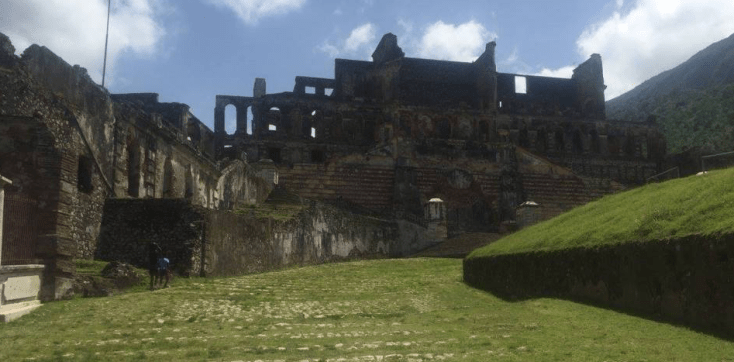

After a thorough walkthrough of the Citadelle, it was time to hike down and check out Palais Sans Souci. Unlike the Citadelle, which lies in remarkable condition, the Palais is literally a shell of its former self. Following the death of Henri I and the assassination of his son shortly thereafter, the Palais became quickly subjected to a considerable amount of looting.

Today, the palace that has been described as a ‘Baroque Versailles’ now lies as a tangle of stone scaffolds, archways, and ruins. Locals hang around the place, hoping to charge visitors a Gourde or two for pointing out ideal photo vantage points, but otherwise, the derelict remains unmolested.

Amiga Island

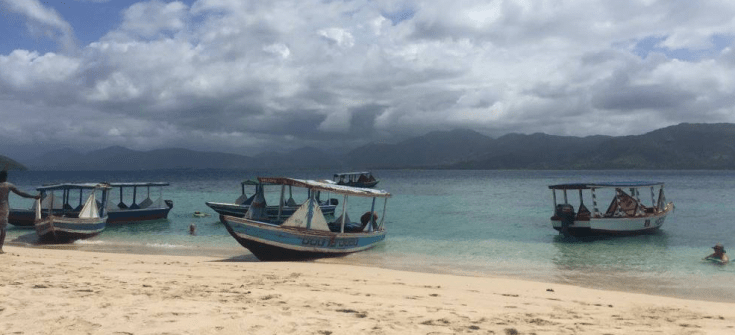

Two-hundred-year-old structures are not the only reasons to visit Cap-Haïtien – the other is natural beauty. Off the coast, northwest of the city, in Acul Bay, lies the picturesque coral island of Ile Rat. To get there, one must catch a motorcycle taxi from the city center to a local fishing village. From there, it is required to charter a boat to get out there. If it seems like I’ve glossed over a detail or two, that’s because I have. When I went to Ile Rat, it was marketed to me as “Amiga Island”.

The island has gone by dual names for centuries. Purportedly, Rat Island had been nicknamed l’île La Amiga, or Friend Island, by Christopher Columbus when he met a hospitable native there. True or not, in recent decades, the name “Amiga island” has become so common that not a single local I spoke to on the journey there responded to that name. While this could easily be chalked up to my lack of knowledge regarding the subtleties of French Creole, it’s much more likely to be due to the influence of Labadee.

Labadee is a peninsula northwest of Cap-Haïtien that is currently leased to Royal Caribbean Cruises Ltd until 2050. Having been in operation in 1986, this resort represents the epitome of ‘out of sight, out of mind’. Surrounded by twelve foot high walls, guarded by a private security force, and supplied exclusively by the cruises that anchor, Labadee is completely separate from greater Haiti. The exception to this is the two hundred locals that are licensed to sell trinkets within the walls.

This disconnect first came to public view in 1991, when it was reported that Royal Caribbean failed to inform passengers that they were actually entering Haiti when disembarking at Labadee. To be true, the peninsula’s various oceanic waterslides, mass kayak lessons, and all-inclusive facade bears little resemblance to the outside world anyhow.

Getting back to my excursion to Amiga Island, I found that a third of the island had been cartoned off for Royal Caribbean passenger activities. The rest of the island, just past the velvet rope barrier, was indeed just as good. White sand, green trees, and blue water, this tiny island — it took 10 mins to walk completely around — was a calendar photographer’s paradise. Of the locals on the island, many were fisherman trying to sell their newly-caught foodstuffs to those like myself, who existed outside the rope barrier.

One such gentleman carried around a full lobster, tied to a piece of cardboard. I must’ve watched him run up and down the beach six times with that poor creature. Another one of these fishermen pointedly asked me, more or less, what I could possibly see myself purchasing. I replied with Lambie, otherwise known as Conche. While he did not have any, he asked me to wait to wait ten minutes. For the duration of that period, I watched him send one of his younger fellows out into the water and find a conch shell or two. After cleaning it, the man brought over a pot, a lime, and pepper sauce. He proceeded then to bash the shells against the pot until the meat was freed.

Despite the proximity to commercial excess, there I was, in the middle of the Caribbean, on a coral island, eating freshly caught Conche. There was nothing not to like. The only exception came when it was time to head back, and my boat driver — with whom I’d prearranged a price — decided to stop in the middle the ocean and ask for more money. Otherwise, it seemed, I had no other option. I’m not new to bald-faced extortion whilst traveling, so the day, as well as the rest of my time in the Cap-Haïtien area, continued unabated following my reluctant agreement.

Ouanaminthe, The Border, and Beyond

Soon, it became time to say farewell to Haiti, and head over the border to the Dominican Republic. Many in my position would fly, bypassing the hassle of a border crossing and the uncertainty that comes with it. Even on a good day, on a stable border, crossing can be both nebulous and subject to the politics of the day. For an example, simply look at either the United States-Mexico or China-Vietnam borders. Haiti and Dominican Republic’s border has never been remotely stable. In fact, relations between the two nations have been historically tense, going back centuries.

To add a level of irony, the border crossing closest to Cap-Haïtien — there are three in total — is that of Ouanaminthe and Dajabon. Between the two towns lies a river that is colloquially known as the Massacre River. Although commonly thought to refer to the Parsley Massacre, in which then-Dominican dictator Rafael Trujillo ordered the deaths of Haitians residing within the Republic, resulting in roughly 12,000 dead, it was indeed a massacre that more than lives up to the river’s name. That said, it would be erroneous to say that one is related to the other. In fact, it refers to thirty French pirates that were murdered by Spanish settlers in the early 18th century.

Of course, this is the border I endeavored to cross. My interest in the Ouanaminthe-Dajabon border was actually two-fold. Not only would I cross the river of such historical import to both sides, but I would also gain the opportunity to see the early stages of that relationship being mended — to the extent it can be, granted.

Every Monday and Friday, since 2010, many of the regulations surrounding the defense of the border are eased. This allows locals on both sides of the river to set up a frontier market on the bridge going over the Massacre River — New developments superseding old ones. Even with such an insurmountable linguistic, cultural, and historical barrier, it was incredible to see both parties figure it out in order to make transactions happen. While it was initially made to happen by the European Union, both sides do it today without such encouragement, give or take the construction of a new bridge a market space.

With that seen and done, I made my way across the bridge, through Dominican Republic immigration, and out onto the other side. They said Haiti was dangerous, chaotic, and not worth my time. They were wrong. Haiti was, and still is, the highlight of my time in the Caribbean, warts and all.